Shelton Stat of the Week

Fifty-eight percent (58%) of people around the world say buying/using eco-friendly products is an important part of their self-image. — Eco Pulse®, 2024 (Global)

I’m facilitating the Friday plenary session at Sustainable Brands’ Brand Led Culture Change event in Minneapolis next week. If you’re not registered for the event, you should be (and you can take care of that here)!

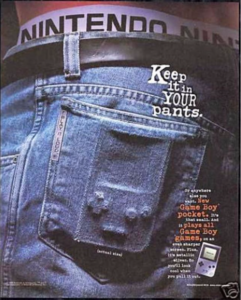

It strikes me that we can’t talk about driving culture change without talking about advertising because the two have always been a mirror of each other. Take a look at the ads below. You’ll be able to quickly – and in some cases, horrifyingly – link them to an era/decade/moment in time in our culture. And the chicken-and-egg question is, of course, which came first, the culture represented in the ad or the ad itself?

(Source material: 43 Vintage Ads That Really Didn’t Age Well (cheezburger.com), Amazing vintage video game ads from the 1980s and 1990s – Rare Historical Photos)

Clearly, sustainability is part of our culture, as the Shelton Stat of the Week points out: 58% of people around the world want to be seen as someone who buys eco-friendly products. In the United States, that number is 46% – up from 33% ten years ago.

But if you take the same approach to sustainability advertising as the advertising industry has taken since the beginning of time, you may well wind up in court – and stumble in the court of public opinion.

With traditional advertising, you can engage in hyperbole. You can be vague. You can say your burger is the best tasting burger in the world, and you don’t have to back it up with why or data or baselines of comparison. In fact, most advertising promises some sort of impossible-to-prove benefit, “buy our product because it will make you cooler, sexier, smarter, friendlier, more efficient, a better person…”.

In many ways, green products aren’t different. The companies advertising them know many people buy them because of the statement it makes about them. And it’s not that you can’t imply those same emotional benefits in your advertising. But you can’t say your product is green – or that your company is green – without backing it up with verifiable data. In other words, you can’t suggest or imply that a product is green with imagery (like a green leaf) and innuendo, and you can’t call a product green just because it’s got some recycled content in the packaging or because it was locally sourced.

Your implicit and explicit messages must be verified so that what you’re saying means what people interpret it to mean. Unilever and Delta are both learning this the hard way. Both companies are doing a LOT of really great work on sustainability; their messaging just wasn’t fact-based enough. In other words, traditional approaches to advertising were applied even though those approaches don’t apply for sustainability.

Join me in Minneapolis next week and we’ll dig further into when and how you can leverage some of the traditional persuasion tools from advertising’s toolbox – and how to effectively drive

View all

View all